The study of the heavens was one of the central features of the Chinese civilization and

the resulting calendar was a sacred document, sponsored and promulgated by the reigning

monarch. For more than two millennia, a Bureau of Astronomy made astronomical

observations, calculated astronomical events such as eclipses, prepared astrological

predictions, and maintained the calendar. After all, a successful calendar not only

served practical needs, but also confirmed the consonance between Heaven and the

imperial court.

Analysis of oldest surviving astronomical records inscribed on oracle bones reveals a

sophisticated Chinese lunisolar calendar, with intercalation of lunar months.

Various intercalation schemes were developed for the early calendars, including the

nineteen-year and 76-year lunar phase cycles that came to be known in the West as

the Metonic cycle and Callipic cycle. From the earliest records, the beginning of

the year occurred at a New Moon near the winter solstice. The choice of month for

beginning the civil year varied with time and place, however. In the late second

century B.C.E., a calendar reform established the practice, which continues today,

of requiring the winter solstice to occur in month 11. This reform also introduced

the intercalation system in which dates of New Moons are compared with the 24 solar

terms. However, calculations were based on the mean motions resulting from the cyclic

relationships. Inequalities in the Moon's motions were incorporated as early as the

seventh century C.E., but the Sun's mean longitude was used for calculating the

solar terms until 1644.

Observing total solar eclipses was, for example, a major element of forecasting the

future health and successes of the Emperor, and astrologers were left with the

onerous task of trying to anticipate when these events might occur. Failure to get

the prediction right, in at least one recorded case in 2300 B.C. resulted in the

beheading of two astrologers.

Chinese civilization, as described in mythology, begins with Pangu, the creator of the

universe, and a succession of legendary sage-emperors and culture heroes

who taught the ancient Chinese to communicate and to find sustenance, clothing, and

shelter. The first prehistoric dynasty is said to be Xia, from about the twenty-first

to the sixteenth century B.C. Until scientific excavations were made at early bronze-age

sites in 1928, it was difficult to separate myth from reality in regard to the Xia.

But since then, and especially in the 1960s and 1970s, archaeologists have uncovered

urban sites, bronze implements, and tombs that point to the existence of Xia civilization

in the same locations cited in ancient Chinese historical texts. At minimum, the Xia

period marked an evolutionary stage between the late neolithic cultures that followed

the settlement of nomadic tribes in the fertile valleys of the Yellow Riverand the subsequent

first Chinese urban civilization of the Shang dynasty.

Chinese civilization, as described in mythology, begins with Pangu, the creator of the

universe, and a succession of legendary sage-emperors and culture heroes

who taught the ancient Chinese to communicate and to find sustenance, clothing, and

shelter. The first prehistoric dynasty is said to be Xia, from about the twenty-first

to the sixteenth century B.C. Until scientific excavations were made at early bronze-age

sites in 1928, it was difficult to separate myth from reality in regard to the Xia.

But since then, and especially in the 1960s and 1970s, archaeologists have uncovered

urban sites, bronze implements, and tombs that point to the existence of Xia civilization

in the same locations cited in ancient Chinese historical texts. At minimum, the Xia

period marked an evolutionary stage between the late neolithic cultures that followed

the settlement of nomadic tribes in the fertile valleys of the Yellow Riverand the subsequent

first Chinese urban civilization of the Shang dynasty.

Thousands of archaeological finds in the Huang He (Yellow River), Henan Valley --the

apparent cradle of Chinese civilization--provide evidence about the Shang dynasty,

which endured roughly from 1700 to 1027 B.C. The Shang dynasty (also called the Yin

dynasty in its later stages) is believed to have been founded by a rebel leader who

overthrew the last Xia ruler. Its civilization was based on agriculture, augmented by

hunting and animal husbandry. Two important events of the period were the development

of a writing system, as revealed in archaic Chinese inscriptions found on tortoise shells

and flat cattle bones (commonly called oracle bones or), and the use of bronze

metallurgy. A number of ceremonial bronze vessels with inscriptions date from the

Shang period; the workmanship on the bronzes attests to a high level of civilization.

Thousands of archaeological finds in the Huang He (Yellow River), Henan Valley --the

apparent cradle of Chinese civilization--provide evidence about the Shang dynasty,

which endured roughly from 1700 to 1027 B.C. The Shang dynasty (also called the Yin

dynasty in its later stages) is believed to have been founded by a rebel leader who

overthrew the last Xia ruler. Its civilization was based on agriculture, augmented by

hunting and animal husbandry. Two important events of the period were the development

of a writing system, as revealed in archaic Chinese inscriptions found on tortoise shells

and flat cattle bones (commonly called oracle bones or), and the use of bronze

metallurgy. A number of ceremonial bronze vessels with inscriptions date from the

Shang period; the workmanship on the bronzes attests to a high level of civilization.

The beginnings of the Chinese calendar can be traced back to the 14th century B.C.E.

Legend has it that the Emperor Huangdi invented the calendar in 2637 B.C.E. The Chinese

calendar is based on exact astronomical observations of the longitude of the sun and the

phases of the moon indicating that the Chinese astronomers of the time were quite capable

of carrying out intricate and detailed observations and calculations.

The beginnings of the Chinese calendar can be traced back to the 14th century B.C.E.

Legend has it that the Emperor Huangdi invented the calendar in 2637 B.C.E. The Chinese

calendar is based on exact astronomical observations of the longitude of the sun and the

phases of the moon indicating that the Chinese astronomers of the time were quite capable

of carrying out intricate and detailed observations and calculations.

The Chinese astronomers were among the earliest to keep systematic record of their

observations of the heavens. Sitings and records of these sitings go back over forty centuries. The

Chinese observed sunspots, meteorites, eclipses and comets which they called "guest stars." They also

observed rare events such as the splitting of comets as the record of 896 CE from the Tang Dynasty

indicates, and meteorite showers. The earliest account of the latter exists in The Chronicles of Zuo Ming

regarding such a shower in 687 BCE.

The Chinese astronomers were among the earliest to keep systematic record of their

observations of the heavens. Sitings and records of these sitings go back over forty centuries. The

Chinese observed sunspots, meteorites, eclipses and comets which they called "guest stars." They also

observed rare events such as the splitting of comets as the record of 896 CE from the Tang Dynasty

indicates, and meteorite showers. The earliest account of the latter exists in The Chronicles of Zuo Ming

regarding such a shower in 687 BCE.

"Here lie the bodies of Ho and Hi, Whose fate, though sad, is risible; Being slain because

they could not spy Th' eclipse which was invisible." - Author unknown

(Refers to the Chinese eclipse of 2136 B.C. or 2159 B.C.)

Because the pattern of total solar eclipses is erratic

in any specific geographic location, many astrologers no doubt lost their heads. By

about 20 B.C., surviving documents show that Chinese astrologers understood what

caused eclipses, and by 8 B.C. some predictions of total solar eclipse were made

using the 135-month recurrence period. By A.D. 206 Chinese astrologers could

predict solar eclipses by analyzing the Moon's motion.

They were also one of the earliest people to make star maps:Shi Shen, an astronomer, catalgied

an eight-volume series of his observations of the heavens in the 4th century BCE. The earliest known

western star maps were made by the Greek astronomer Hiparchus in 2 BCE.

They were also one of the earliest people to make star maps:Shi Shen, an astronomer, catalgied

an eight-volume series of his observations of the heavens in the 4th century BCE. The earliest known

western star maps were made by the Greek astronomer Hiparchus in 2 BCE.

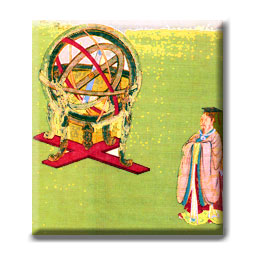

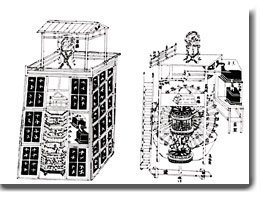

In addition to their observations and records of the heavens, the Chinese also developed highly

sophisticated navigational systems based on the stars. Chinese sailors in the third century BCE were

already able tofind their bearings using the Great Dipper and the North Pole. In conjunction with their

observations of the heavens the Chinese also built planetariums, and various instruments including

armillaries for measuring the celestial coordinates. Scientists reading the records estimate that the

Chinese were probably using an armillary to map the heavens by the 4th century BCE.

In addition to their observations and records of the heavens, the Chinese also developed highly

sophisticated navigational systems based on the stars. Chinese sailors in the third century BCE were

already able tofind their bearings using the Great Dipper and the North Pole. In conjunction with their

observations of the heavens the Chinese also built planetariums, and various instruments including

armillaries for measuring the celestial coordinates. Scientists reading the records estimate that the

Chinese were probably using an armillary to map the heavens by the 4th century BCE.

In Chinese history, the study of astronomy was inseparable from mathematics. From the earliest times, the Chinese, according to Joseph Needham, were far in advance of of contemporary civilizations such as those of Egypt, Babylon, Greece and Rome. There is evidence for instance, that the Chinese had mastered the decimal system since the dawn of history. The earliest treatise on mathematics, Zhoubi suanjing was proably written during the Zhou Dynasty between 1030-1022 BCE. During the Han Dynasty (221BCE-220CE) several mathematical treatises were compiled by distinguished mathemeticians such as Liu Hui whose Haidao suanjing (The Sea and Island Mathematical Manual) appeared sometime around 220CE.

The dual studies in astronomy and mathematics would result in the some of the most remarkable

inventions including the astronomical clock by the astronomer Su Song over nine hundred years ago. In

the second century CE the famous astronomer Shang Heng devised a mobile water-driven globe which

revolved in correspondence with the movements of the heavenly bodies.

The dual studies in astronomy and mathematics would result in the some of the most remarkable

inventions including the astronomical clock by the astronomer Su Song over nine hundred years ago. In

the second century CE the famous astronomer Shang Heng devised a mobile water-driven globe which

revolved in correspondence with the movements of the heavenly bodies.

|

|