Modern cosmology, or the study of the Universe, has come into its own only in the last century. This period, and particularly in the last half-century, has seen astonishing progress -- starting with Einstein's General Theory of Relativity and culminating, at the end of the twentieth century with the emergence of a coherent view of the universe: the "Hot Big Bang" model. This model successfully explains a remarkably broad range of observations and while this model has never claimed to represent the final truth, it nonetheless provides a cogent framework for understanding the cosmos from the earliest few fractions of a second of its existence till the present. Along the way, we have learnt that intuitions and common sense have a tendency to mislead us quite dramatically, from our perception of an unmoving Earth, to our persistent belief in the absoluteness and inflexibility of space and time. Nevertheless, we can transcend these human limitations and arrive at a picture of the universe that is a much closer description of the way it truly is:

In the beginning there was neither space nor time as we know them, but a shifting foam of strings and loops, as small as anything can be. Within the foam, all of space, time and energy mingled in a grand unification. But the foam expanded and cooled. And then there was gravity, and space and time, and a universe was created.

There was a grand unified force that filled the universe with a false vacuum endowed with a negative pressure.

This caused the universe to expand exceedingly rapidly against gravity. But this state was unstable and did not last, and the true vacuum reappeared, the inflation stopped, and the grand unified force was gone forever. In its place were the strong and electroweak interactions, and enormous energy from the decay of the false vacuum.

The universe continued to expand and cool, but at a much slower rate. Families of particles, matter and antimatter, rose briefly to prominence and then died out as the temperature fell below that required to sustain them.

Then the electromagnetic and the weak interaction were cleaved, and later the neutrinos were likewise separated from the photons. The last of the matter and antimatter annihilated, but a small remnant of matter remained.

The first elements were created, reminders of the heat that had made them. And all this came to pass in three minutes, after the creation of time itself.

Thereafter the universe, still hot and dense and opaque to light, continued to expand and cool. Finally the electrons joined to the nuclei, and there were atoms, and the universe became transparent. The photons which were freed at that time continue to travel even today as relics of the time when atoms were created, but their energy drops ever lower.

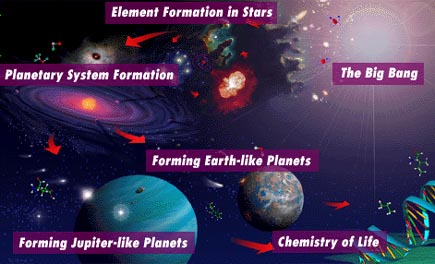

And a billion years passed after the creation of the universe, and then the clouds of gas collapsed from their own gravity, and the stars shone and there were galaxies to light the universe.

And some galaxies harbored at their centers giant black holes, consuming much gas and blazing with exceeding brightness.

And still the universe expanded. And stars created heavy elements in their cores, and then they exploded, and the heavy elements went out into the universe. New stars form still and take into themselves the heavy elements from the generations that went before them.

And more billions of years passed, and one particular star formed, like many others of its kind that had already formed and would form in the future. Around this star was a disk of gas and dust.

And it happened that this star formed alone, with no companion close by to disrupt the disk, so the dust did condense and formed planets and numerous smaller objects.

And the third planet was the right size and the right distance from its star so that rain fell upon the planet and did not boil away, nor did it freeze. And this water made the planet warm, but not too warm, and was yet a good solvent, and many compounds formed.

And some of these compounds could make copies of themselves. And these compounds made a code that could be copied and passed down to all the generations. And then there were cells, and they were living, and billions of years elapsed with only the cells upon the planet.

Then some of the cells joined together and made animals which lived in the seas of the planet. And finally some cells from the water began to live upon the rocks of the land, and they joined together and made plants. And the plants made oxygen, and other creatures from the seas began to live upon the land.

And many millions of years passed, and multitudes of creatures lived, of diverse kinds, each kind from another kind.

And a kind of animal arose and spread throughout the planet, and this animal walked upon two feet and made tools. And it began to speak, and then it told stores of itself, and at last it told this story.

But all things must come to their end, and after many billions of years, the star will swell up and swallow the third planet, and all will be destroyed in the fire of the star.

And we know not how the universe will end, but it may expand forever, and finally all the stars will die and the universe will end in eternal darkness and cold.

Is this a myth? If we define a myth as a narrative of explanation, it

would qualify.

Is this a myth? If we define a myth as a narrative of explanation, it

would qualify.

Indeed, some non-specialists equate the Big Bang model with a contemporary creation myth. But there are two fundamental differences between creation myths and the Big Bang narrative. First, the Big Bang model was not designed to explain the "place of human beings" in the grand scheme of things; it was developed in order to understand the evolution of the Universe as outcome of the physical laws that govern the natural world. The presence or absence of human beings is irrelevant.

Moreover, the above narrative is highly detailed and even then, the fanciful description is extremely condensed; the complete version of this story is the subject of this entire course and then, we will only scratch the surface.

Nevertheless, if all you knew of this explanation was a tale such as that written above, you might have difficulty in distinguishing it from a story of ants in the tree of life. This story, however, differs fundamentally from the earlier myths. The most important distinction is the way in which this explanation was developed. It was based upon many centuries of observations of the universe and its contents. It draws upon the experience and thoughts of generations of thinkers, but always the most significant factor has been the accumulation and interpretation of observations. The story is held to a set of stringent constraints; it must explain known facts, and it must hold together as a coherent narrative, all the parts fitting like pieces of a grand jigsaw puzzle.

The success or failures of scientific cosmologies does not depend on the human whims, preferences or philosophical bents. Scientific cosmologies are based upon and judged by data, the measurements obtained by direct, objective observations of the universe. Failure to account for the observations is fatal, resulting in the model being consigned to the trashbin of history. In science, the cumulative evidence of data is the final arbiter.

Having differentiated between scientific cosmologies and creation myths, it is important to note that the myths revolve around concepts that held, and still hold, a powerful sway over the human psyche. This is illustrated by the special fascination that cosmological beginnings and endings continue to hold.

Based solely upon most immediate observations, there is no particular reason to believe that the universe must have a beginning or an end; on the scale of human life, the Earth and sky seem eternal and unchanging. Yet it is also true that seasons begin and end, plants develop and wither, and animals and humans are born and die. Perhaps then, the universe too has a beginning and an end.

Not all mythologies assume this, nor do all modern scientific models. Even among scientists of the twentieth century, preferences for one model over another have sometimes been based more upon philosophical beliefs than upon data. A distaste for the Big Bang or for an infinite expansion is an emotional choice based upon a personal mythology. When the big bang model was first introduced, many of the most prominent scientists of the day reacted quite negatively; such an abrupt beginning for the cosmos was uncomfortable for the older generation. Still others interpreted the big bang as scientific vindication for the existence of a creator. Today the big bang is well accepted on its own objective merits, but now some discussions of the possible end of the universe carry an echo of the aesthetics of the cosmologist. Regardless of such intrusions of human wishes, the major difference between science and mythology stands: as noted above, in science, the cumulative evidence of data must be the final arbiter.

|

|