The earliest civilization in Europe appeared on the coasts and islands of the

Aegean Sea. This body of water is a branch of the Mediterranean Sea. It is

bounded by the Greek mainland on the west, Asia Minor (now Turkey) on the

east, and the island of Crete on the south.

The earliest civilization in Europe appeared on the coasts and islands of the

Aegean Sea. This body of water is a branch of the Mediterranean Sea. It is

bounded by the Greek mainland on the west, Asia Minor (now Turkey) on the

east, and the island of Crete on the south.

The first people to inhabit the Aegean region migrated in waves from the Near East and Central Europe roughly between 10,000 and 3,000 B.C. In time, two different civilizations flourished in this region from about 3000 BC to 1000 BC. The earliest is known as Minoan, because its center at Knossos (also spelled Cnossus) on the island of Crete was the legendary home of King Minos, who was (according to mythology) the son of the god Zeus and Europa, a Phoenician princess.

The Minoans developed sea trade across the Aegean Sea to Anatolia and the Near-East, including the Egyptian and Babylonia empires, eventually venturing as far as Western Spain. Crete became the prominent political and economic center of the Greek world. However, in the 14th century BCE, a severe earthquake (and it is now presumes, subsequent tidal wave) severly damaged Minoan cities on Crete as well as its structure and stability. Soon after, they were conquered by a rival power based on the Mainland.

The latter are known as the Mycenaeans, or Achaeans. This group had invaded

the Greek mainland between 1900 BC and 1600 BC, and the term Achaeans was

sometimes used to refer to all Greeks of this period. The center of their

culture was Mycenae, a city on the Greek peninsula named the Peloponnesus.

Mycenae flourished from about 1500 to 1100 BC and was the capital of the

region ruled by King Agamemnon, the Achaean leader in the Trojan War.

The war against Troy took place in the 13th or early 12th century BC.

The latter are known as the Mycenaeans, or Achaeans. This group had invaded

the Greek mainland between 1900 BC and 1600 BC, and the term Achaeans was

sometimes used to refer to all Greeks of this period. The center of their

culture was Mycenae, a city on the Greek peninsula named the Peloponnesus.

Mycenae flourished from about 1500 to 1100 BC and was the capital of the

region ruled by King Agamemnon, the Achaean leader in the Trojan War.

The war against Troy took place in the 13th or early 12th century BC.

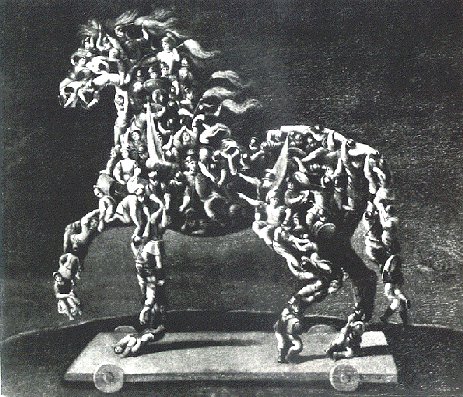

In the years preceeding the Trojan War, the Mycenaeans had assumed assumed the political and militaric status of master of the eastern Mediterranean. It was during this golden age of splendor that the culture and religious traditions of the classical Greek civilization began to take form. This is the Homeric, or Heroic Age, because the culture and values of the latter part of this period are those permanently embodied in the Homeric poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Soon afterward, the Mycenaeans civilization declined. Whether this was caused by civil wars or the Dorian invasion (The Dorians were said to be the descendants of Heracles - known today by his Latin name, Hercules, a hero celebrated by all Greeks. The children of Heracles had been driven from Greece by the evil king Eurystheus (king of Mycenae and Tiryns, who compelled Heracles to undertake his famous labors) but eventually returned to reclaim their patrimony by force. Some scholars regard the myth of the Dorians as a distant memory of historical invaders who overthrew the Mycenaean civilization. In any case, the Dorians were said to have conquered virtually all of Greece, with the exception of Athens and the islands of the Aegean. The pre-Dorian populations from other parts of Greece were said to have fled eastward, many of them relying on the help of Athens.) is still an open question. What does appear to be clear is that in the turmoil, the Greek civilization entered its Dark Age. It has been argued that even script disappeared. Be that as it may, this period also coincides with migrations to Asia Minor or what came to be known as Ionia.

According to Greek legend, it was in this age that the Oedipus tragedy

evolved, and the story later depicted in Aeschylus' Oresteia was played out.

This was the time of the famous Trojan War, which left the Trojans and Greeks

alike bereft of some of their most beloved and courageous men who died as heroes

on the incarnadine battle fields. This was the time of the wonderings of Aeneas and

Odysseus after the war, and a time where the inhabitants of Mount Olympus interacted

with the humans more than ever.

According to Greek legend, it was in this age that the Oedipus tragedy

evolved, and the story later depicted in Aeschylus' Oresteia was played out.

This was the time of the famous Trojan War, which left the Trojans and Greeks

alike bereft of some of their most beloved and courageous men who died as heroes

on the incarnadine battle fields. This was the time of the wonderings of Aeneas and

Odysseus after the war, and a time where the inhabitants of Mount Olympus interacted

with the humans more than ever.

Homer himself did not live during the time period which is named after him. He is believed to have lived three hundred years after the Homeric Age of which he wrote about in his epic poems. He is, of course, our most important literary source for knowledge of this period, combining the history, religion, myth, and lore of many generations.

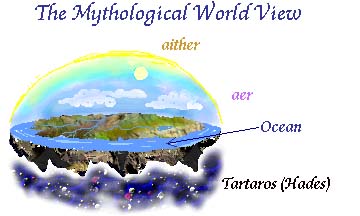

There are hints of the Greek conception of the universe in Homer's two epics. For Homer,

heaven is a solid inverted bowl straddling the earth, with fiery, gleaming aether above

the cloud-bearing air. Homer mentions the movements of sun, moon, and many stars by name.

The fact that Hades is on the underside of earth has an important impact on conceptions

of heaven: it is unlit by the sun, therefore, the sun--and by extension, other

heavenly bodies-- must sink only to the level of Ocean, which is conceived as a river

circling earth's edge. From it the Sun must also rise--though how it gets back to the

eastern bank of Ocean is never explained.

There are hints of the Greek conception of the universe in Homer's two epics. For Homer,

heaven is a solid inverted bowl straddling the earth, with fiery, gleaming aether above

the cloud-bearing air. Homer mentions the movements of sun, moon, and many stars by name.

The fact that Hades is on the underside of earth has an important impact on conceptions

of heaven: it is unlit by the sun, therefore, the sun--and by extension, other

heavenly bodies-- must sink only to the level of Ocean, which is conceived as a river

circling earth's edge. From it the Sun must also rise--though how it gets back to the

eastern bank of Ocean is never explained.

These popular conceptions of sky are more fully explained in Hesiod, whose works on gods and on agriculture and animal-herding are more closely connected to the practical application of astronomy. He clocks spring, summer, and harvest by solstices and the rising and setting of certain stars, and notices that the sun migrates southwards in winter. Night is a substance welling up from under the earth, as if it were a dark flowing mist.

One early and popular cult, that of Orpheus, developed its own of gods and universe-creation variant from those in Homer and Hesiod; there, a primeval egg is birthed by the early gods, and the upper half of its broken shell becomes heaven's vault. Various cults, cities and tribes of Greeks (who were unified only by language and common culture, and both of these had regional variants) probably had different versions of cosmogony and slightly different gods in charge of astronomical movement, but the general physical conception of the sky is alluded to by many authors of plays and other popular works, and was probably held by the majority of people.

It was the Greek outposts in Asia Minor and the islands that witnessed the beginnings of

what was to become classical Greek civilization. These areas were relatively peaceful and

settled; more important, they had direct contact with the older, wealthy, more sophisticated

cultures of the east. Inspired by these cross-cultural contacts, the Greek settlements of

Asia Minor and the islands saw the birth of Greek art, architecture, religious and

mythological traditions, law, philosophy, and poetry, all of which received direct

inspiration from the Near East and Egypt. The earliest known Greek poets and philosophers

are associated with Asia Minor and the islands, the most prominent of all being Homer

whose poetry is composed in a highly artificial mixed dialect but is predominately Ionic.

It is not surprising that, by the sixth century, these Ionians began to develop new ideas

about the sky they steered by. The most fundamental of these was that the universe might

run, not only by the whim of gods, but by physical, mechanical rules and principles that

might, through study, be understood and predicted.

mythological traditions, law, philosophy, and poetry, all of which received direct

inspiration from the Near East and Egypt. The earliest known Greek poets and philosophers

are associated with Asia Minor and the islands, the most prominent of all being Homer

whose poetry is composed in a highly artificial mixed dialect but is predominately Ionic.

It is not surprising that, by the sixth century, these Ionians began to develop new ideas

about the sky they steered by. The most fundamental of these was that the universe might

run, not only by the whim of gods, but by physical, mechanical rules and principles that

might, through study, be understood and predicted.

Our sources for all early Greek astronomy are scant, none more so than for Thales supposedly the first of the philosophers. Thales is believed to have lived in the city of Miletus, near the coast of w hat is now Turkey, around 585 B.C. It is generally asserted that the crucial contribution of Thales to scientific thought was the discovery of nature. That is, that the natural phenomena we see around us are explicable in terms of matter interacting by natural laws, and are not the results of arbitrary acts by gods. An example is Thales' theory of earthquakes. Thales conceived of the earth as flat and floating on a vast ocean. Earthquakes, he asserted, are disturbances in that ocean which occasionally cause the earth to shake or even crack, just as they would a large boat. (Recall the Greeks were a seafaring nation.) The common Greek belief at the time was that the earthquakes were caused by the anger of Poseidon, god of the sea.

Of the Various inventions and discoveries are attributed to Thales, the most famous is his prediction of an eclipse of 585. Modern scholars are fairly sure he was able to do this by consulting known Babylonian eclipse and lunar observations going back about 150 years, long enough to notice that eclipses recur after about 18 years. His activities also seem to have included star-observations and trigonometry, which he is credited with having founded, but the details of his theories are either lost or obscured by later legends about this early thinker who left no written record.

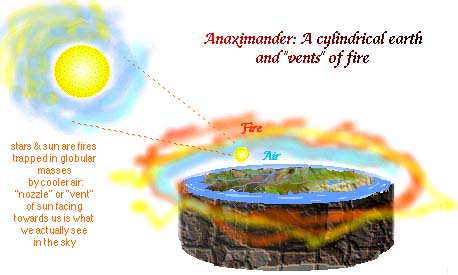

In about 555 B.C., Thales was followed by another great Milesian thinker, Anaximander.

Anaximander suggested that the earth was actually a cylinder circled by concentric

rotating cylinders of air and fire. The heavenly bodies, the sun, the moon, the stars,

are described as wheels of fire located on these cylinders. He argued that the observed

light from these objects is only a small fraction, that which is visible through holes or

vents in the intervening cylinders. Eclipses and lunar variations are due to the vents

opening and closing. Although in his conception of how the concentric cylinders came to be

we find echoes of the early cosmologies, the model itself represents among the first known

attempts to explain the scheme in purely physical--in fact, in mathematical--terms.

This is the first recorded attempt at a mechanical model of the universe.

Even positing that the sun and stars were rings of fire was revolutionary as all heavenly

bodies had previously been regarded as living gods.

In about 555 B.C., Thales was followed by another great Milesian thinker, Anaximander.

Anaximander suggested that the earth was actually a cylinder circled by concentric

rotating cylinders of air and fire. The heavenly bodies, the sun, the moon, the stars,

are described as wheels of fire located on these cylinders. He argued that the observed

light from these objects is only a small fraction, that which is visible through holes or

vents in the intervening cylinders. Eclipses and lunar variations are due to the vents

opening and closing. Although in his conception of how the concentric cylinders came to be

we find echoes of the early cosmologies, the model itself represents among the first known

attempts to explain the scheme in purely physical--in fact, in mathematical--terms.

This is the first recorded attempt at a mechanical model of the universe.

Even positing that the sun and stars were rings of fire was revolutionary as all heavenly

bodies had previously been regarded as living gods.

Both Thales and Anaximander struggled with the puzzle of the origin of the universe, what was here

at the beginning, and what things are made of. Thales suggested that in the beginning there was only

water, so somehow everything was made of it. Anaximander supposed that initially there was a

boundless chaos, and the universe grew from this as from a seed.

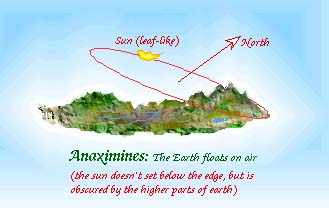

Anaximines of Miletus (c. 525 BCE), the third of the great Ionian thinkers had, what some argue to be,

a more sophisticated approach. He suggested that all things are produced through a process of gradual

condensation and "rarification": earth condenses out of air, and fire is "exhaled" from the earth. In the

process, he refined the flat-earth hypothesis, proposing that the earth and heavenly bodies are not

only flat but loft on infinite air like a leaf. He also argued that celestial bodies do not set

beneath the earth, as in mythology, but instead turn at an angle (the axis of rotation, after all,

is visible to us in the northern part of the sky) so that many are obscured by the "higher"

parts of earth to the north.

Anaximines of Miletus (c. 525 BCE), the third of the great Ionian thinkers had, what some argue to be,

a more sophisticated approach. He suggested that all things are produced through a process of gradual

condensation and "rarification": earth condenses out of air, and fire is "exhaled" from the earth. In the

process, he refined the flat-earth hypothesis, proposing that the earth and heavenly bodies are not

only flat but loft on infinite air like a leaf. He also argued that celestial bodies do not set

beneath the earth, as in mythology, but instead turn at an angle (the axis of rotation, after all,

is visible to us in the northern part of the sky) so that many are obscured by the "higher"

parts of earth to the north.

While all these theories may seem naive, the main thing to note is that the gods are just not mentioned in analyzing these phenomena. There is an emergence of the view that nature is a dynamic entity evolving in accordance with some admittedly not fully understood laws, but no t being micromanaged by a bunch of gods using it to vent their anger or whatever on hapless humanity. Moreover, it would appear that an essential part of the Milesians' success in developing their picture of nature was that they engaged in open, rational, critical debate about each others ideas. It was tacitly assumed that all the theories and explanations were directly competitive with one another, and all should be open to public scrutiny, so that they could be debated and judged. This is laid the foundation for science as we know it and it is still the way scientists work.

Step by step, the "Presocratic" philosophers began to refine, specialize, develop, and apply the

systems of empirical observation and deduction which their predecessors had invented. Some, like

Parmenides and Zeno, concentrated on exposing the fallacies and logical traps to which the

first uses of analytical thinking often fell prey. Others, like followers of the semi-legendary

Pythagoras, used their theories about how the universe worked to develop new ideas of divinity,

astronomy, universal harmony, and mathematics, and extended these ideas to dictate a proper,

"harmonious" lifestyle.

Step by step, the "Presocratic" philosophers began to refine, specialize, develop, and apply the

systems of empirical observation and deduction which their predecessors had invented. Some, like

Parmenides and Zeno, concentrated on exposing the fallacies and logical traps to which the

first uses of analytical thinking often fell prey. Others, like followers of the semi-legendary

Pythagoras, used their theories about how the universe worked to develop new ideas of divinity,

astronomy, universal harmony, and mathematics, and extended these ideas to dictate a proper,

"harmonious" lifestyle.

Pythagoras was born about 570 B.C. on the island of Samos, less than a hundred miles from Miletus,

and was thus a contemporary of Anaximenes. However, the island of Samos was ruled by a tyrant named

Polycrates, and to escape an unpleasant regime, Pythagoras moved to Croton, a Greek town in southern

Italy, about 530 B.C. There, Pythagoras founded what we would nowadays call a cult, a religious

group with strict rules about behavior and a belief in the immortality of the soul and

reincarnation in different creatures. In particular,

The Pythagoreans believed strongly that numbers, by which they meant the positive integers 1,2,3, ...,

had a fundamental, mystical significance. The numbers were a kind of eternal truth, perceived by the

soul, and not subject to the uncertainties of perception by the ordinary senses. In fact, they thought

that the numbers had a physical existence, and that the universe was somehow constructed from them.

In support of this, they pointed out that

different musical notes differing by an octave or a fifth, could be produced by pipes (like a flute), whose lengths were in the ratios of whole numbers, 1:2 and 2:3 respectively. Note that this is an

experimental verification of an hypothesis. They also felt that the motion of the heavenly bodies

must somehow be a perfect harmony, giving out a music we could not hear since it had been with us

since birth. Interestingly, they did not consider the earth to be at rest at the center of the universe.

They thought it was round, and orbited about a central point daily, to account for the motion of the stars.

In a sense, the Pythagoreans were the first to propose a non-geocentric system. To them, humanity and

earth were imperfect, and only by sacrifice and a strict regimen of personal conduct could one strive

to reach the divine. Accordingly, they placed the divine, poetically called the "Hearth of the Universe"

or "Throne of Zeus", at the center of a finite, spherical universe. The sun is a glass sphere that

catches and reflects this hearth-light. A counter-earth had to be invented, supposedly to make the

number of planetary spheres ten. These include the five visible planets out through Saturn, earth,

the moon, the sun, and the heavenly sphere on which were the stars. It has been suggested that

the counter-earth was invented to account for the frequency of lunar eclipses. The counter-earth

also solves a major problem in this view, serving to eclipse the Hearth-Fire so that we never look

God in the face, so to speak. The concepts of number, harmony, and music all influenced the

Pythagoreans to invent this fully-realized version of the concentric celestial orbits, which resonate

with "the music of the spheres".

that the numbers had a physical existence, and that the universe was somehow constructed from them.

In support of this, they pointed out that

different musical notes differing by an octave or a fifth, could be produced by pipes (like a flute), whose lengths were in the ratios of whole numbers, 1:2 and 2:3 respectively. Note that this is an

experimental verification of an hypothesis. They also felt that the motion of the heavenly bodies

must somehow be a perfect harmony, giving out a music we could not hear since it had been with us

since birth. Interestingly, they did not consider the earth to be at rest at the center of the universe.

They thought it was round, and orbited about a central point daily, to account for the motion of the stars.

In a sense, the Pythagoreans were the first to propose a non-geocentric system. To them, humanity and

earth were imperfect, and only by sacrifice and a strict regimen of personal conduct could one strive

to reach the divine. Accordingly, they placed the divine, poetically called the "Hearth of the Universe"

or "Throne of Zeus", at the center of a finite, spherical universe. The sun is a glass sphere that

catches and reflects this hearth-light. A counter-earth had to be invented, supposedly to make the

number of planetary spheres ten. These include the five visible planets out through Saturn, earth,

the moon, the sun, and the heavenly sphere on which were the stars. It has been suggested that

the counter-earth was invented to account for the frequency of lunar eclipses. The counter-earth

also solves a major problem in this view, serving to eclipse the Hearth-Fire so that we never look

God in the face, so to speak. The concepts of number, harmony, and music all influenced the

Pythagoreans to invent this fully-realized version of the concentric celestial orbits, which resonate

with "the music of the spheres".

Over the next century or so, 500 B.C.-400 B.C., the main preoccupation of philosophers in the Greek world was that when we look around us, we see things changing all the time. How is this to be reconciled with the feeling that the universe must have some constant, eternal qualities? Heraclitus, from Ephesus, claimed that "everything flows", and even objects which appeared static had some inner tension or dynamism. Parminedes, an Italian Greek, came to the opposite conclusion, that nothing ever changes, and apparent change is just an illusion, a result of our poor perception of the world. This may not sound like a very promising debate, but in fact it is, because, in trying to analyze what is changing and what isn't in the physical world, the Greeks were led to the idea of elements, atoms forces of attraction and repulsion, and conservation laws, like the conservation of matter.

In the fourth century B.C., Greek intellectual life centered increasingly in Athens, where first Plato and then Aristotle established schools, the Academy and the Lyceum respectively, and attracted philosophers and scientists from all over Greece.

The basic foundations of what we today call "Modern Science" was laid down by the Aegeians. Their momentous first attempts were carried forward by the Athenian School, followed by the Islamic scholars who brought together Indian, Persian, Chinese, Greek, and Arab scholars and scientists, be they Jews, Christians, Buddhists and Muslims to bring about a flowering of intellectual activity that dominated the world for nearly 1000 years. They infused the world of "Natural Philosophy" with notions of experimentation and empiricism, and pushed forward the idea of using mathematical models to describe the workings of nature, creating the necessary conditions for the gestation of Modern Astronomy and Cosmology.

|

|