|

|

|

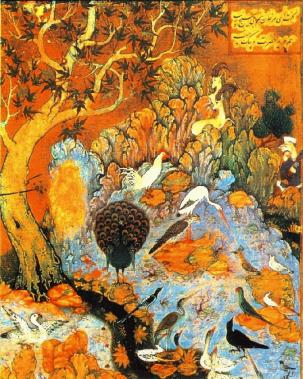

The last in the line of

the Abrahamic family of revealed traditions, Islam emerged in the early

decades of the seventh century. Its message, addressed in perpetuity, calls upon

a people that are wise, a people of reason, to seek in their daily life, in

the rhythm of nature, in the ordering of the universe, in their own selves,

in the very diversity of humankind, signs that point to the Creator and

Sustainer of all creation, Who alone is worthy of their submission. Revealed to Prophet Muhammad (s.a.s.) in

Arabia, its influence spread rapidly and strongly, bringing within its fold,

in just over a century after its birth, inhabitants of the lands stretching

from the central regions of Asia to the Iberian peninsula in Europe. A major

world religion, Islam today counts a quarter of the globe's population among

its adherents. Contrary to popular misperceptions, Muslims are not a

monolithic mass of people, all marching to the same drum. Within its fundamental unity, Islam has, over the

ages, elicited varying responses to its primal message calling upon man to

surrender himself to God. These

responses, emerging from the unfolding of the timeless message of Islam over

time and geography, encompass a vibrant breadth of interpretations, spiritual

temperaments, juridical preferences, social and psychological dispositions

and political entities, as well as the rich multiplicity of ethnic, cultural,

linguistic plurality that human beings are heir to. Shia Ismailism is one such response. The last in the line of

the Abrahamic family of revealed traditions, Islam emerged in the early

decades of the seventh century. Its message, addressed in perpetuity, calls upon

a people that are wise, a people of reason, to seek in their daily life, in

the rhythm of nature, in the ordering of the universe, in their own selves,

in the very diversity of humankind, signs that point to the Creator and

Sustainer of all creation, Who alone is worthy of their submission. Revealed to Prophet Muhammad (s.a.s.) in

Arabia, its influence spread rapidly and strongly, bringing within its fold,

in just over a century after its birth, inhabitants of the lands stretching

from the central regions of Asia to the Iberian peninsula in Europe. A major

world religion, Islam today counts a quarter of the globe's population among

its adherents. Contrary to popular misperceptions, Muslims are not a

monolithic mass of people, all marching to the same drum. Within its fundamental unity, Islam has, over the

ages, elicited varying responses to its primal message calling upon man to

surrender himself to God. These

responses, emerging from the unfolding of the timeless message of Islam over

time and geography, encompass a vibrant breadth of interpretations, spiritual

temperaments, juridical preferences, social and psychological dispositions

and political entities, as well as the rich multiplicity of ethnic, cultural,

linguistic plurality that human beings are heir to. Shia Ismailism is one such response.

|

|

|

|

|

|

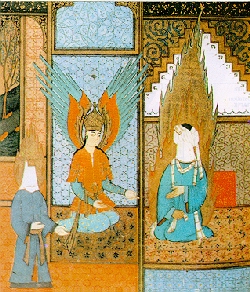

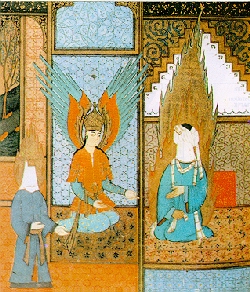

Like all Muslims, the

Ismailis affirm the unity of God as the first and foremost article of the

faith, followed by that of Divine guidance through God's chosen messengers, of

whom Prophet Muhammad was the last. The verbal attestation of the absolute

unity and transcendence of God and of His choice of Muhammad as His Messenger

constitutes the profession of faith, and the basic creed of all Muslims. Beyond this, the Ismailis maintain, as do

all Shia, that while the Revelation ceased at the Prophet's death, the need

for spiritual and moral guidance of the community, through an ongoing

interpretation of the Islamic message, continued. They assert that the Prophet invested his authority through

designation onto Ali, his cousin, the husband of his daughter and only

surviving child, Fatima, and his first supporter who had devoutly championed

the cause of Islam and had earned the Prophet's trust and admiration. This concept of qualified and rightly

guided leadership is rooted, first and foremost, in the Quran and further

reinforced by Prophetic traditions, the most prominent of which is the

Prophet’s sermon, following his farewell pilgrimage, designating Ali as his

successor, and his testament that he was leaving behind him "the two

weighty things", namely the Quran and his progeny, for the future

guidance of the community. Like all Muslims, the

Ismailis affirm the unity of God as the first and foremost article of the

faith, followed by that of Divine guidance through God's chosen messengers, of

whom Prophet Muhammad was the last. The verbal attestation of the absolute

unity and transcendence of God and of His choice of Muhammad as His Messenger

constitutes the profession of faith, and the basic creed of all Muslims. Beyond this, the Ismailis maintain, as do

all Shia, that while the Revelation ceased at the Prophet's death, the need

for spiritual and moral guidance of the community, through an ongoing

interpretation of the Islamic message, continued. They assert that the Prophet invested his authority through

designation onto Ali, his cousin, the husband of his daughter and only

surviving child, Fatima, and his first supporter who had devoutly championed

the cause of Islam and had earned the Prophet's trust and admiration. This concept of qualified and rightly

guided leadership is rooted, first and foremost, in the Quran and further

reinforced by Prophetic traditions, the most prominent of which is the

Prophet’s sermon, following his farewell pilgrimage, designating Ali as his

successor, and his testament that he was leaving behind him "the two

weighty things", namely the Quran and his progeny, for the future

guidance of the community.

|

|

|

|

|

|

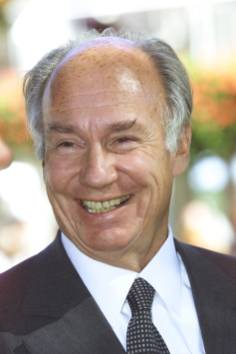

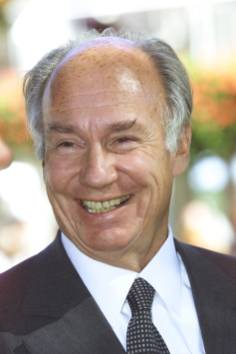

Throughout their history,

the Ismailis have been led by a living Imam, tracing the line of Imamat in

hereditary succession from Ali to His Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan, who is

the 49th Imam in direct lineal descent from Prophet Muhammad through Ali and

Fatima. The Ismailis comprehend Islam

through the guidance of the Imam of the time, who is the inheritor of the

Prophet's authority, and the trustee of his legacy. The principal function of the Imam is to enable the believers

to go beyond the apparent or outward form of the Revelation in search of its

spirituality and wisdom. According to

the Ismailis, Islam – or submission – in its pristine sense refers to the

inner struggle of an individual to engage fully in the journey of this

earthly life and yet, with the guidance of the Alid Imam, to rise above its

trappings in search of the Divine. The succession of the line of prophecy by

that of the Imamat ensures this balance between the exoteric aspect of the

faith and its esoteric, spiritual essence. Neither the exoteric nor the

esoteric obliterates the other. While the Imam is the path to a believer's inward,

spiritual elevation, he is also the authority who makes the outward form of

the religion relevant according to the needs of time. The inner, spiritual life in harmony with

the exoteric, is a dimension of the faith that finds acceptance among many

groups within Islam. Throughout their history,

the Ismailis have been led by a living Imam, tracing the line of Imamat in

hereditary succession from Ali to His Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan, who is

the 49th Imam in direct lineal descent from Prophet Muhammad through Ali and

Fatima. The Ismailis comprehend Islam

through the guidance of the Imam of the time, who is the inheritor of the

Prophet's authority, and the trustee of his legacy. The principal function of the Imam is to enable the believers

to go beyond the apparent or outward form of the Revelation in search of its

spirituality and wisdom. According to

the Ismailis, Islam – or submission – in its pristine sense refers to the

inner struggle of an individual to engage fully in the journey of this

earthly life and yet, with the guidance of the Alid Imam, to rise above its

trappings in search of the Divine. The succession of the line of prophecy by

that of the Imamat ensures this balance between the exoteric aspect of the

faith and its esoteric, spiritual essence. Neither the exoteric nor the

esoteric obliterates the other. While the Imam is the path to a believer's inward,

spiritual elevation, he is also the authority who makes the outward form of

the religion relevant according to the needs of time. The inner, spiritual life in harmony with

the exoteric, is a dimension of the faith that finds acceptance among many

groups within Islam.

|

|

|

|

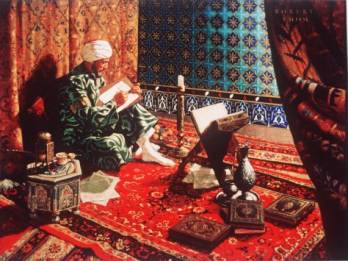

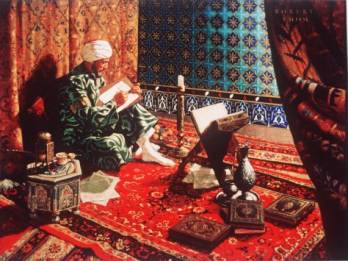

For an Ismaili, the quest

for harmony requires the engagement of not only the spirit but also the

intellect. Indeed, the human

intellect is viewed as a precious Divine gift and a fundamental facet of

religion. Its role has never been seen in terms of a

confrontation between Revelation and reason. Rooted in the teachings of Imams Ali and Jaffer as-Sadiq, the

Ismailis have historically emphasized the complementarity between Revelation

and intellectual reflection – including the study of the Physical Universe –

each substantiating the other and both providing different perspectives into

the mystery of God’s creation.

Indeed, over the course of their 1400-year-old history, the Ismailis and

the Ismaili Imams have encouraged natural and philosophical inquiry, and

promoted the culture of unhindered scientific thought through generous

patronage of luminaries such as the jurist al-Nu'man, the physicist Ibn

Haytham, astronomers Ali bin Yunus and al-Tusi, and philosophers Nasir-i-Khusraw

and Ibn Sina, to name but a few. Many

of these were Ismailis themselves. In

keeping with this tradition, exploring the frontiers of knowledge through

scientific and other endeavours, and facing up to the challenges of ethics

posed by an evolving world is, thus, seen as a requirement of the faith. For an Ismaili, the quest

for harmony requires the engagement of not only the spirit but also the

intellect. Indeed, the human

intellect is viewed as a precious Divine gift and a fundamental facet of

religion. Its role has never been seen in terms of a

confrontation between Revelation and reason. Rooted in the teachings of Imams Ali and Jaffer as-Sadiq, the

Ismailis have historically emphasized the complementarity between Revelation

and intellectual reflection – including the study of the Physical Universe –

each substantiating the other and both providing different perspectives into

the mystery of God’s creation.

Indeed, over the course of their 1400-year-old history, the Ismailis and

the Ismaili Imams have encouraged natural and philosophical inquiry, and

promoted the culture of unhindered scientific thought through generous

patronage of luminaries such as the jurist al-Nu'man, the physicist Ibn

Haytham, astronomers Ali bin Yunus and al-Tusi, and philosophers Nasir-i-Khusraw

and Ibn Sina, to name but a few. Many

of these were Ismailis themselves. In

keeping with this tradition, exploring the frontiers of knowledge through

scientific and other endeavours, and facing up to the challenges of ethics

posed by an evolving world is, thus, seen as a requirement of the faith.

|

|

|

|

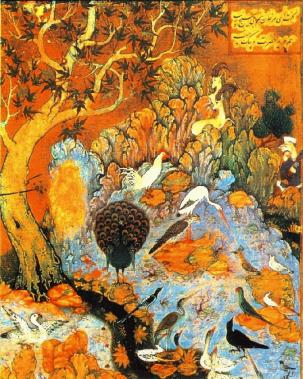

Consonant with the role of

the intellect is the responsibility of individual conscience, both of which

inform the Ismaili tradition of tolerance and celebration of plurality. In fact, the Ismaili belief in the Divine

endorsement, as revealed in the Holy Quran, of religiously and culturally

plural human societies and of the salvific value of other monotheistic

religions, is in stark contrast to, for example, the beliefs of the Wahhabi

movement, a contemporary Islamic revivalist school whose exclusivist

discourse preaches a monolithic puritanical interpretation of Islam and the

establishment of its hegemony over all other interpretations and faiths. Such views not only violate the Quranic

injunction “There is no compulsion in religion” but are also tragically

incongruent with the needs of the emerging global village in which relations

between different peoples are best fostered on the basis of equality and

mutual respect. Consonant with the role of

the intellect is the responsibility of individual conscience, both of which

inform the Ismaili tradition of tolerance and celebration of plurality. In fact, the Ismaili belief in the Divine

endorsement, as revealed in the Holy Quran, of religiously and culturally

plural human societies and of the salvific value of other monotheistic

religions, is in stark contrast to, for example, the beliefs of the Wahhabi

movement, a contemporary Islamic revivalist school whose exclusivist

discourse preaches a monolithic puritanical interpretation of Islam and the

establishment of its hegemony over all other interpretations and faiths. Such views not only violate the Quranic

injunction “There is no compulsion in religion” but are also tragically

incongruent with the needs of the emerging global village in which relations

between different peoples are best fostered on the basis of equality and

mutual respect.

|

|

|

|

The

Ismailis hold that Muslims are commanded to be a community of the middle path

and of balance, a community that avoids extremes and that enjoins good and

forbids evil using the best of arguments, a community that eschews compulsion

and leaves each to their own faith while encouraging all to vie for

goodness. And this imperative of

“balance” that forms the web which

binds the community to the individual, and the individual to the

community. Indeed, an individual’s

spiritual and intellectual quest is only meaningful in tandem with an effort

to act – here and now – on the moral imperative to do good by offering a

helping hand to the vulnerable and those less fortunate, and to promote

justice, tolerance and social equity.

In the final analysis, it is the nobility of being – of spirit, of

mind and of conduct – that endears one in the sight of God.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|